Today's Modern world keeps talking about "multi tenancy" ( Each user/Customer is a tenant), "virtualization" , dockers, containers, hypervisor etc.. In this post, i will explain these terminologies.

What is virtualization?

In computing, virtualization refers to the act of creating a virtual (rather than actual) version of something, including virtual computer hardware platforms, operating systems, storage devices, and computer network resources.

It allows you to run multiple operating system as virtual machines.Each copy of operating system is installed in to a virtual Machine.

From the above figure, it shows as partitioning one physical server into multiple virtual servers. Each of these virtual servers can run its own operating system and applications, and perform as if it is an individual server.

What is Hypervisor?

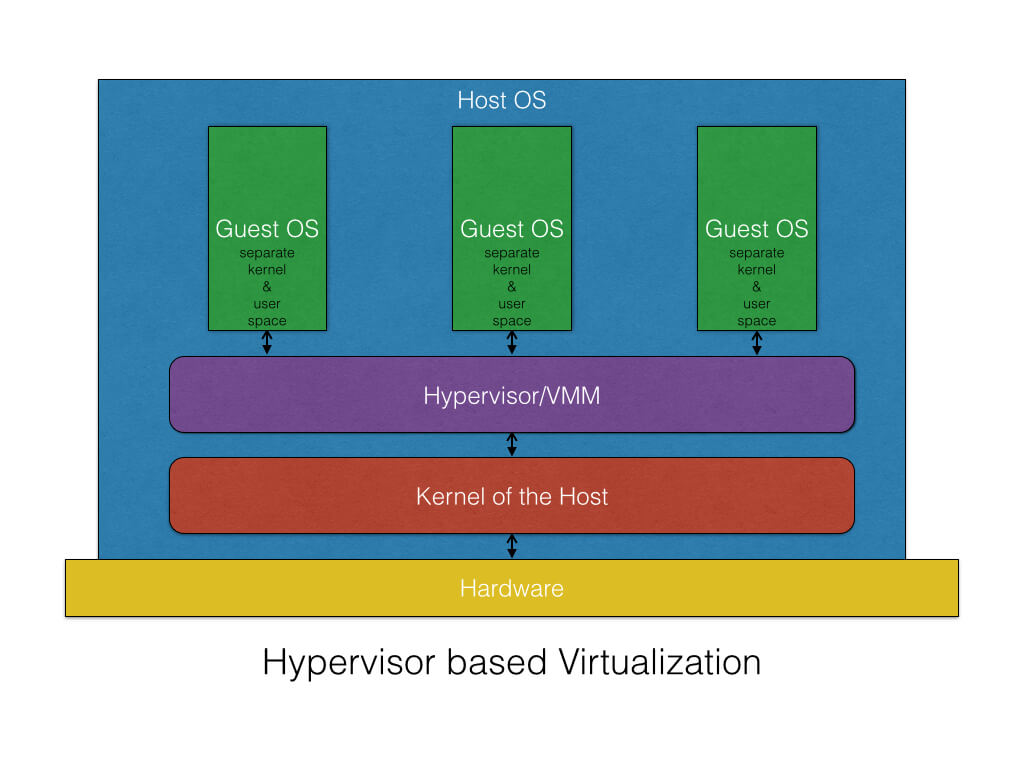

A hypervisor or virtual machine monitor (VMM) is a piece of computer software, firmware or hardware that creates and runs virtual machines.

A computer on which a hypervisor runs one or more virtual machines is called a host machine, and each virtual machine is called a guest machine.

Multiple instances of a variety of operating systems may share the virtualized hardware resources: for example, Linux, Windows, and OS X instances can all run on a single physical x86 machine.

This contrasts with operating-system-level virtualization, where all instances (usually called containers) must share a single kernel, though the guest operating systems can differ in user space, such as different Linux distributions with the same kernel.

Hypervisors are often divided between Type 1 and Type 2 hypervisors.

A Type 1 hypervisor (sometimes called a ‘Bare Metal’ hypervisor) runs directly on top of the physical hardware. Each guest operating system runs atop the hypervisor. Xen is perhaps the canonical example. KVM, Xen, or ESXi.

A Type 2 hypervisor (sometimes called a ‘Hosted’ hypervisor) runs inside an operating system which in turn runs on the physical hardware. Each guest operating system then runs atop the hypervisor. Desktop virtualization systems often work in this manner. Examples: VMWARE, Oracle Virtual Box etc.

What is Linux Namespace?

Before discussing about Linux Namespace, check out the below question.

How do i provide an isolated view of global resources to a group of processes(tasks).

The Answer is Namespace.

Linux Namespace means - Process Virtualization. In order words, makes processes running inside that namespace believe they have their own instance of that resource.

"Def: From Linux article:

Namespaces Wraps global system resources in an abstraction that makes it appear to the processes that they have their own isolated instance of the global resource.

Namespace isolation is the key technology that makes containers possible on Linux. There are six namespaces in Linux:

- mount: Isolates the filesystems visible to a group of processes, similar to the chroot command.

- UTS: Isolates host and domain names so that each namespace can have its own. (UTS = Unix Time Sharing)

- IPC: Isolates System V and POSIX message queue interprocess communication channels. (IPC = InterProcess Communication)

- PID: Lets processes in different PID namespaces have the same PID. (This is useful in containers, as it lets each container have its own init (PID 1) and allows for easy migration between systems. ) (PID = Process ID)

- network: Enables each network namespace to have its own view of the network stack, including network devices, IP addresses, routing tables etc.

- user: Allows a process to have a different UID and GID inside a namespace to what it has outside

Here i would like to present about on Network Namespace, since it been using in Cloud technologies (Such as Openstack).

What is Network Namespace?

Network namespaces allow you to have isolated network environments on a single host.

Each network namespace has its own interfaces and routing table, separated from other namespaces. In addition, processes on your system can be associated with a specific network namespace.

(or)

With network namespaces, you can have different and separate instances of network interfaces and routing tables that operate independent of each other.

The network namespaces provides your own view of the network stack of your system. In Linux, the namespace concept is supported by “ip netns” command.

Network namespace used in a variety of projects such as Open Stack, Docker

To check if your kernel supports namespaces, run the following commands:

Creating a network namespace is actually quite easy. Just use this command:

ip netns add <new namespace name>

For example, let’s say you wanted to create a namespace called “blue”. You’d use this command:

ip netns add blue

To verify that the network namespace has been created, use this command:

ip netns list

With namespaces, every tenant network traffic and network interfaces is completely isolated from each other as illustrated.

Network Namespaces are powerful constructs in Linux that allows you to create a copy of the TCP/IP network stack

What is Cgroups ?

Cgroups - Called as Control Groups. As name says, it controls or manages the subsystems (or processes) in terms of resources.

It is a Linux kernel feature to limit, account, and isolate resource usage (CPU, memory, disk I/O, etc.) of process groups.

From the definition Redhat,

Cgroups allow you to allocate resources — such as CPU time, system memory, network bandwidth, or combinations of these resources — among user-defined groups of tasks (processes) running on a system.

You can monitor the cgroups you configure, deny cgroups access to certain resources, and even reconfigure your cgroups dynamically on a running system. The

cgconfig (control group config) service can be configured to start up at boot time and reestablish your predefined cgroups, thus making them persistent across reboots

By using cgroups, system administrators gain fine-grained control over allocating, prioritizing, denying, managing, and monitoring system resources. Hardware resources can be appropriately divided up among tasks and users, increasing overall efficiency.

Source from [https://mairin.wordpress.com/2011/05/13/ideas-for-a-cgroups-ui/]

So this diagram kind of shows how four of the system resources that cgroups can control – CPU, memory, network, and storage I/O – could be cut into slices that are then combined into two groups – the yellow and the purple one – which make up virtual OSes. Say I gave cgroup #1 (yellow) to Sally, and cgroup #2 (purple) to Joe. Whenever Sally starts a process, you could set it to only run on the CPUs that are members of cgroup #1 (via cpuset), at whatever priority level is set for those CPUs (via cpu). It’ll only be able to use as much memory as was allocated to cgroup #1, only be able to use as much network and I/O bandwidth as cgroup #1 is able to use. When Joe starts a process, because he’s part of cgroup #2, he won’t be using the same CPUs as Sally. He may have more or less memory, I/O, and network bandwidth allocated to him.

It’s kind of / sort of like Joe and Sally are using different computers, on the same operating system. Cool, right?

How to Create Control group?

There are a collection of tools available in the libcgroup-tools package, including cgcreate, for example. You can use this tool to create a new cgroup as follows:

cgcreate -g memory,cpu:mysql

This will create a new cgroup called mysql which has been tied to the memory and cpu subsystems.

What is Container ?

cgroups : manage resources for groups of processes

namespaces : per process resource isolation

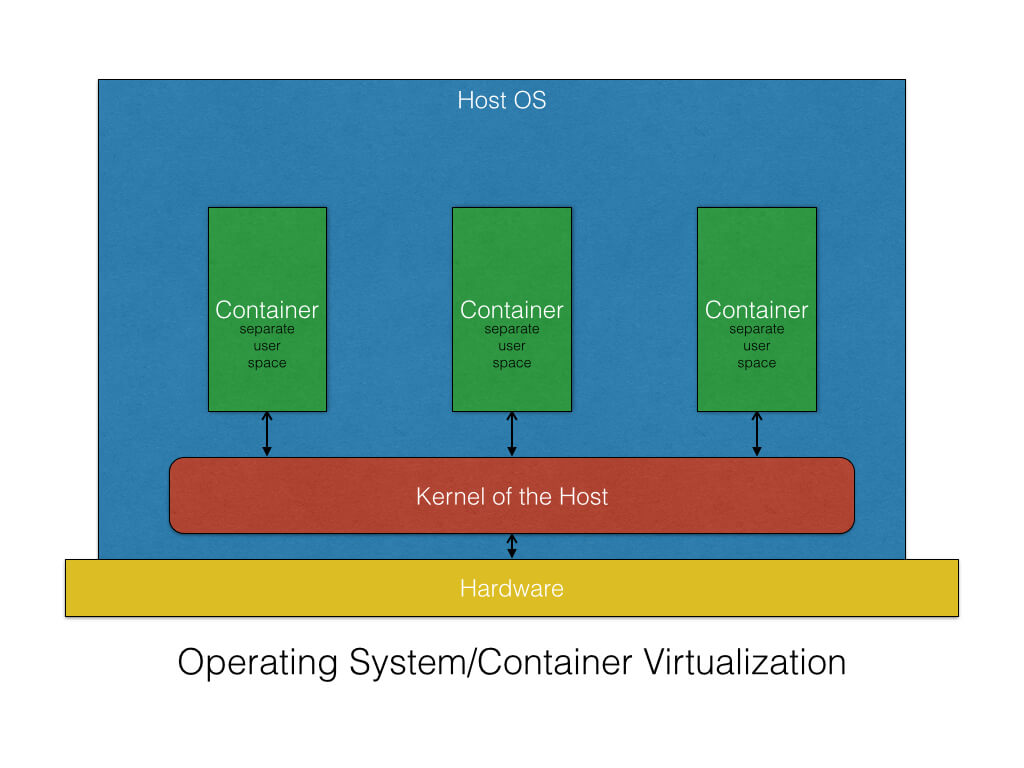

Container is - Operating system virtualization.

Linux Containers (LXC) is an operating-system-level virtualization method for running multiple isolated Linux systems on a single control host (LXC host).

It does not provide a virtual machine, but rather provides a virtual environment that has its own CPU, memory, block I/O, network, etc. space and the resource control mechanism.

Containers which offer an environment as close to possible as the one you'd get from a VM but without the overhead that comes with running a separate kernel and simulating all the hardware.

This is achieved through a combination of kernel security features such as namespaces, mandatory access control and control groups.

Another View ->

The difference between a container and a full-fledged VM is that all containers share the same kernel of the host system. This gives them the advantage of being very fast with almost 0 performance overhead compared with VMs. They also utilize the different computing resources better because of the shared kernel. However, like everything else, sharing the kernel also has its set of shortcomings.

Type of containers that can be installed on the host should work with the kernel of the host. Hence, you cannot install a Windows container on a Linux host or vice-versa.

Isolation and security -- the isolation between the host and the container is not as strong as hypervisor-based virtualization since all containers share the same kernel of the host

What is Docker?

COMPARING CONTAINERS AND VIRTUAL MACHINES

Containers and virtual machines have similar resource isolation and allocation benefits -- but a different architectural approach allows containers to be more portable and efficient.

VIRTUAL MACHINES

Virtual machines include the application, the necessary binaries and libraries, and an entire guest operating system -- all of which can amount to tens of GBs.

CONTAINERS

Containers include the application and all of its dependencies --but share the kernel with other containers, running as isolated processes in user space on the host operating system. Docker containers are not tied to any specific infrastructure: they run on any computer, on any infrastructure, and in any cloud.

Dockers

Docker containers are not tied to any specific infrastructure: they run on any computer, on any infrastructure, and in any cloud.

Docker is able run to different application in a isolated environment on top of one operating system and yet they don't need all the overhead of an entire operating system.

For Example:

An App that is running Java 7 and at the same time you have a brand new API's taking

advantage of the new capabilities in java 8 and you can run these two side by side

on the exact same machine with our needing install or worried about having multiple

versions of java installed.

You can create their own containers that they run inside of it are isolated from each other.

Source from [https://docs.docker.com/engine/understanding-docker/]

Dockers Platform [ refer the above link for much Information]

Because of the lightweight nature of containers, which run without the extra load of a hypervisor, you can run more containers on a given hardware combination than if you were using virtual machines.

Docker provides tooling and a platform to manage the lifecycle of your containers:

- Encapsulate your applications (and supporting components) into Docker containers

- Distribute and ship those containers to your teams for further development and testing

- Deploy those applications to your production environment, whether it is in a local data center or the Cloud

What is Docker Engine?

Docker Engine is a client-server application with these major components:

- A server which is a type of long-running program called a daemon process.

- A REST API which specifies interfaces that programs can use to talk to the daemon and instruct it what to do.

- A command line interface (CLI) client.

The CLI uses the Docker REST API to control or interact with the Docker daemon through scripting or direct CLI commands. Many other Docker applications use the underlying API and CLI. The daemon creates and manages Docker objects, such as images, containers, networks, and data volumes.

What is Docker’s architecture?

Docker uses a client-server architecture. The Docker client talks to the Docker daemon, which does the heavy lifting of building, running, and distributing your Docker containers. The Docker client and daemon can run on the same system, or you can connect a Docker client to a remote Docker daemon. The Docker client and daemon communicate via sockets or through a REST API.

Docker client:

This is what's running in our machine. It's the docker binary that we interface with when we open a terminal and type

$ docker pull or $ docker run. It connects to the docker daemon which does all the heavy-lifting, either in the same host (in the case of Linux) or remotely (in our case, interacting with our VirtualBox VM).Docker daemon:

This is what does the heavy lifting of building, running, and distributing your Docker containers.

Docker Images:

Docker images are the blueprints for our applications. They are our blueprints for actually building a real instance of them. An image can be an OS like Ubuntu, but it can also be an Ubuntu with your web application and all its necessary packages installed.

Docker Container:

Docker containers are created from docker images, and they are the real instances of our containers/lego bricks. They can be started, run, stopped, deleted, and moved.

Docker Images Vs Docker Container:

If an image is a class, then a container is an instance of a class—a runtime object.

An instance of an image is called container. You have an image, which is a set of layers as you describe. If you start this image, you have a running container of this image. You can have many running containers of the same image.

You can see all your images with

docker images whereas you can see your running containers with docker ps (and you can see all containers with docker ps -a).Docker Hub:

Docker Hub is the official Docker hosted registry that can hold Docker Images. Docker Hub is the official registry

How to install Docker in Ubuntu:

[ Source from https://www.digitalocean.com/community/tutorials/how-to-install-and-use-docker-getting-started]

Update the repository with the new addition:

sudo apt-get update

Finally, download and install docker:

sudo apt-get install docker-engineHow To Use Docker

Once you have docker installed, its intuitive usage experience makes it very easy to work with. By now, you shall have the docker daemon running in the background. If not, use the following command to run the docker daemon.

To run the docker daemon:

sudo docker -d &

Usage Syntax:

Using docker (via CLI) consists of passing it a chain of options and commands followed by arguments. Please note that docker needs sudo privileges in order to work.

sudo docker [option] [command] [arguments]

Note: Below instructions and explanations are provided to be used as a guide and to give you an overall idea of using and working with docker. The best way to get familiar with it is practice on a new VPS. Do not be afraid of breaking anything– in fact, do break things! With docker, you can save your progress and continue from there very easily.

Beginning

Let's begin with seeing all available commands docker have.

Ask docker for a list of all available commands:

sudo dockerattach Attach to a running container

build Build a container from a Dockerfile

commit Create a new image from a container's changes

cp Copy files/folders from the containers filesystem to the host path

diff Inspect changes on a container's filesystem

events Get real time events from the server

export Stream the contents of a container as a tar archive

history Show the history of an image

images List images

import Create a new filesystem image from the contents of a tarball

info Display system-wide information

insert Insert a file in an image

inspect Return low-level information on a container

kill Kill a running container

load Load an image from a tar archive

login Register or Login to the docker registry server

logs Fetch the logs of a container

port Lookup the public-facing port which is NAT-ed to PRIVATE_PORT

ps List containers

pull Pull an image or a repository from the docker registry server

push Push an image or a repository to the docker registry server

restart Restart a running container

rm Remove one or more containers

rmi Remove one or more images

run Run a command in a new container

save Save an image to a tar archive

search Search for an image in the docker index

start Start a stopped container

stop Stop a running container

tag Tag an image into a repository

top Lookup the running processes of a container

version Show the docker version information

wait Block until a container stops, then print its exit code

Check out system-wide information and docker version:

# For system-wide information on docker: sudo docker info # For docker version: sudo docker version

Docker represents a company and this company offers a registry of images.

If you think of how virtualization works, we need to have a disk image that represents the system we are running on.

Docker registry is a registry of already existing images that we can use to run and create containerized application.

There is whole lot of community and whole lot of work that's been done to system.

Docker company supports and maintains this registry and community around it.

How to search for the Images?

Go to -> https://registry.hub.docker.com

and search for software's (e.g: python). You will get the multiple copies. And find one that which is required.

Working with Images

As we have discussed at length, the key to start working with any docker container is using images. There are many freely available images shared across docker image index and the CLI allows simple access to query the image repository and to download new ones.

When you are ready, you can also share your image there as well. See the section on “push” further down for details.

Searching for a docker image:*

# Usage: sudo docker search [image name]

sudo docker search ubuntu

Docker search command allows us to actually go look at that registry and searching for the images that we want with out needing up a browser.

This will provide you a very long list of all available images matching the query: Ubuntu.

How to search for the images using docker command?docker search --help:docker search -s 100 <Software> e.g: docker search -s 100 pythonWhat will happen once we find an image that you like?

Downloading (PULLing) an image:

Either when you are building / creating a container or before you do, you will need to have an image present at the host machine where the containers will exist.

Docker has "pull" command, it will go up to the website and grab the image and download to your local machine The format of docker command as:

Either when you are building / creating a container or before you do, you will need to have an image present at the host machine where the containers will exist.

Docker has "pull" command, it will go up to the website and grab the image and download to your local machine The format of docker command as:

# Usage: sudo docker pull [image name]

docker pull <software>:tag

If we don't give the tag(version of software), then it will try to download all the versions of the images.

# Usage: sudo docker pull [image name] sudo docker pull ubuntu

Then it will download all versions of Ubuntu like 12.04, 13.04 etc...

There is a way to download the latest version of software using keyword called "latest"

There is a way to download the latest version of software using keyword called "latest"

e.g: sudo docker pull ubuntu:latest

How to check the list of images:

All the images on your system, including the ones you have created by committing (see below for details), can be listed using “images”. This provides a full list of all available ones.

# Example: sudo docker images

sudo docker images

REPOSITORY TAG IMAGE ID CREATED VIRTUAL SIZE

my_img latest 72461793563e 36 seconds ago 128 MB

ubuntu 12.04 8dbd9e392a96 8 months ago 128 MB

ubuntu latest 8dbd9e392a96 8 months ago 128 MB

ubuntu precise 8dbd9e392a96 8 months ago 128 MB

ubuntu 12.10 b750fe79269d 8 months ago 175.3 MB

ubuntu quantal b750fe79269d 8 months ago 175.3 MB

What needs to be done after downloading the images?

Then play with "run" command.

Creating a New Container

It is currently not possible to create a container without running anything (i.e. commands). To create a new container, you need to use a base image and specify a command to run.

# Usage: sudo docker run [image name] [command to run]

sudo docker run my_img echo "hello"

# To name a container instead of having long IDs

# Usage: sudo docker run -name [name] [image name] [comm.]

sudo docker run -name my_cont_1 my_img echo "hello"

How to "run" command in interactive mode?This will output "hello" and you will be right back where you were. (i.e. your host's shell)As you can not change the command you run after having created a container (hence specifying one during "creation"), it is common practice to use process managers and even custom launch scripts to be able to execute different commands.

Usage: sudo docker run -it(interactive) [image name] [command to run on the image]

e.g: sudo docker run -it centOS:latest /bin/bash

What docker will do is:

It will create the container with that image and executes the bash command.

e.g: docker run -it centos:latest /bin/bash Then you can use as centos machine.bash-4.2$ /cat/redhat-releasecentOS 2.6

How to exit from the image:

exit

It runs only one entry point of the command (/bin/bash). Once we exit from the bash, then container stopped.Working with Containers

When you "run" any process using an image, in return, you will have a container. When the process is notactively running, this container will be a non-running container. Nonetheless, all of them will reside on your system until you remove them via rm command.

Listing all current containers:

By default, you can use the following to list all running containers:

sudo docker ps

To have a list of both running and non-running ones, use:

sudo docker ps -l sudo docker ps -aMore on docker run - Command

This command will create a new container and execute command with in that container . This container will remain until it is explicitly deleted.

A container can be restarted, attached, start or stopped. But we can't change the command that is executed.

Whenever the container is restarted, the command which ran earlier still present always.

docker run -i busybox sh -> The console may not be seen but we can run the commands.

Running a container:

When you create a container and it stops (either due to its process ending or you stopping it explicitly), you can use “run” to get the container working again with the same command used to create it.

# Usage: sudo docker run [container ID]

sudo docker run c629b7d70666

Remember how to find the containers? See above section for listing them.

Stopping a container:

To stop a container's process from running:

# Usage: sudo docker stop [container ID]

sudo docker stop c629b7d70666

Saving (committing) a container:

If you would like to save the progress and changes you made with a container, you can use “commit” as explained above to save it as an image.

This command turns your container to an image.

Remember that with docker, commits are cheap. Do not hesitate to use them to create images to save your progress with a container or to roll back when you need (e.g. like snapshots in time).

Removing / Deleting a container:

Using the ID of a container, you can delete one with rm.

# Usage: sudo docker rm [container ID]

sudo docker rm c629b7d70666docker rm $(dockers ps -aq) -> To remove all container ID'sThere is automatic way of deleting the container after executing the docker command.

docker run -it --rm <image> <command>

e.g: docker run -it --rm busybox sh

Then check for any dockers exist or not.

e.g: docker ps -a

Committing changes to an image:

As you work with a container and continue to perform actions on it (e.g. download and install software, configure files etc.), to have it keep its state, you need to “commit”. Committing makes sure that everything continues from where they left next time you use one (i.e. an image).

# Usage: sudo docker commit [container ID] [image name]

sudo docker commit 8dbd9e392a96 my_img

Sharing (PUSHing) images:

Although it is a bit early at this moment - in our article, when you have created your own container which you would like to share with the rest of the world, you can use push to have your image listed in the index where everybody can download and use.

Please remember to “commit” all your changes.

# Usage: sudo docker push [username/image name]

sudo docker push my_username/my_first_image

Note: You need to sign-up at index.docker.io to push images to docker index.

How to share the folders from present working directory of Host Machine and docker container?

Use "-v" option to share folders between host machine and docker

# Usage:

docker run -it --rm -v [Host Machine :Docker Container Directory] [image Name] [Command]# Example:

docker run -it --rm -v /home/muni:/hostdirectory ubuntu /bin/bash$ touch file.txt

The "file.txt" is shared across the docker container and Host system. But if we verify the permissions of this file and it would be root.

How to change the permissions of the file which is shared between docker and host system?

Use "-u" option to share folders between host machine and docker

# Example:

docker run -it --rm -v /home/muni:/hostdirectory -u 1000:1000 ubuntu /bin/bash

Use "-e" option to pass the environment variables in dockers

# Usage:

docker run -it --rm -e [ENVIRONMENT VARIABLES] [image Name] [Command]# Example:

docker run -it --rm -e MYNAME=MUNI ubuntu /bin/bash

$ echo $MYNAME

MUNIWhen a host system has deprecated libraries or it doesn't support software's need for compilation (or)

You don't want to install any software in Host system (or ) some time run environment is not matching.

In all above cases, docker shall help to run the program(code) in the container and get the output in the host system.

# Usage:

docker run -it --rm -v [Host:/docker] -u [permissions] [image] [command] -o [outputfile]# Usage:

docker run -it --rm -v ($pwd):/go -u 1000:1000 golang:latest go build -o Helloworld.outHow to pass port arguments in run command and run in back ground?

"-d" is used to run the process in background.

"-p" is used to pass the port arguments.

# Usage:

docker run -d -p [port number] [image]# Usage:

docker run -d -p 80 nginx